Nellie's Baby (COPY) (COPY) (COPY) (COPY) (COPY) (COPY) (COPY) (COPY)

Where ‘those sorts of people’ were sent

The last of the ‘lunatic asylums’ closed only 20 years ago. They were founded on ideas of paternalism and social progress and survived on the basis they offered safety. But as William Ray explains, they delivered decades of harm.

Listen to the Nellie’s Baby

podcast now on

Apple

Spotify

iHeartRadio

or wherever you find podcasts

There were 70 men, each of them taken out of bed, stripped, then marched naked through the halls of the hospital to the shower block.

“They were showered en masse by nursing staff who were wearing rubbers and gumboots,” says Dr Olive Webb, who saw it happen.

“They were then taken out and dried and then herded back to the lobby where the clothes were.

“Concentration camps came to mind.”

Webb was a psychologist at Christchurch’s Sunnyside Hospital in the 1970s.

In 2022, she gave testimony about the treatment of mentally disabled patients at the hospital to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in State Care.

Sunnyside Hospital in Christchurch, in 1977. Photo: Supplied / Kevin Hill, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Sunnyside Hospital in Christchurch, in 1977. Photo: Supplied / Kevin Hill, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The sort of daily indignity Webb described is far from the worst to have been shared with the commission. Testimony from former patients highlighted the routine use of electric shock therapy as a punishment, beatings and sexual assault.

The RNZ podcast Nellie’s Baby follows one woman’s search for information about her mother, who gave birth to her while in the Porirua Asylum. In the process, she learns about the conditions of such institutions that existed in the very recent past.

In her evidence to the commission, Webb did not point the finger at individual staff.

“Hand on heart I have not seen an individual staff person being cruel” she said. “But the systems in which everybody lived and worked were terribly cruel. You had one group of people who had the power of life and death and daily activity, and every single piece of power that you could wish to have, completely dominating another group who had absolutely no power at all.”

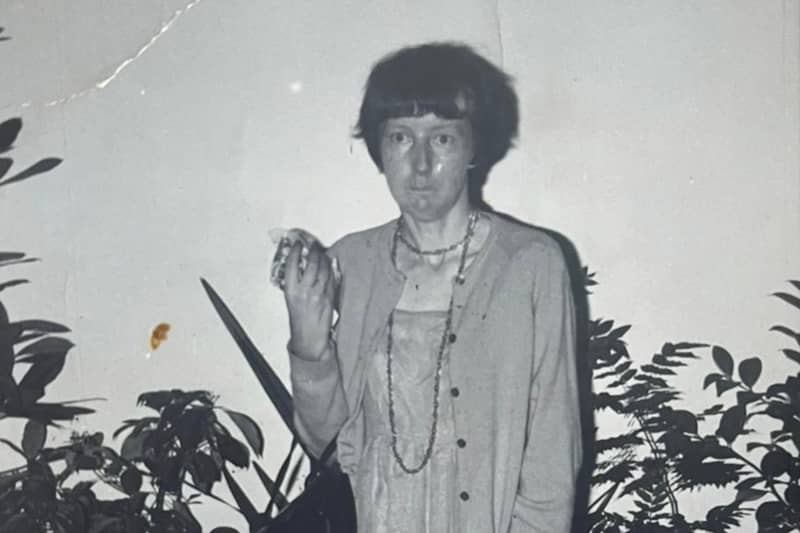

Dr Olive Webb. Photo: Supplied

Dr Olive Webb. Photo: Supplied

Patients were ushered through into a small day room - “and there they sat.”

“And did nothing?” asked the commission’s lawyer.

“Did nothing,” Webb confirmed.

“You've described that in your statement as a complete removal of thinking, creativity, dignity and independence?”

“Yes.”

“Why do you think that was deemed acceptable at the time?” the commission’s lawyer asked.

“I think it's about the value systems of the day,” Webb responded.

“You know, this was considered to be an appropriate place for ‘these people’, and ‘these sorts of people’... They had no value.”

The idea for asylums

Where did this value system come from? Whose idea was it to set up these mental institutions, where so many would be abused and neglected over the decades?

New Zealand’s history of institutionalisation starts in 1846, when colonial authorities passed a so-called “Lunatic Ordinance”. Following the lead of similar laws in the UK, the ordinance allowed anyone certified as a “lunatic” by two doctors and a magistrate to be locked up in a hospital or prison.

But with the colonial population rising rapidly, hospitals and jails couldn’t meet demand. In 1854, New Zealand's first purpose-built “lunatic asylum” was opened in Wellington. Over the next 20 years, public asylums were built in all our major population centres.

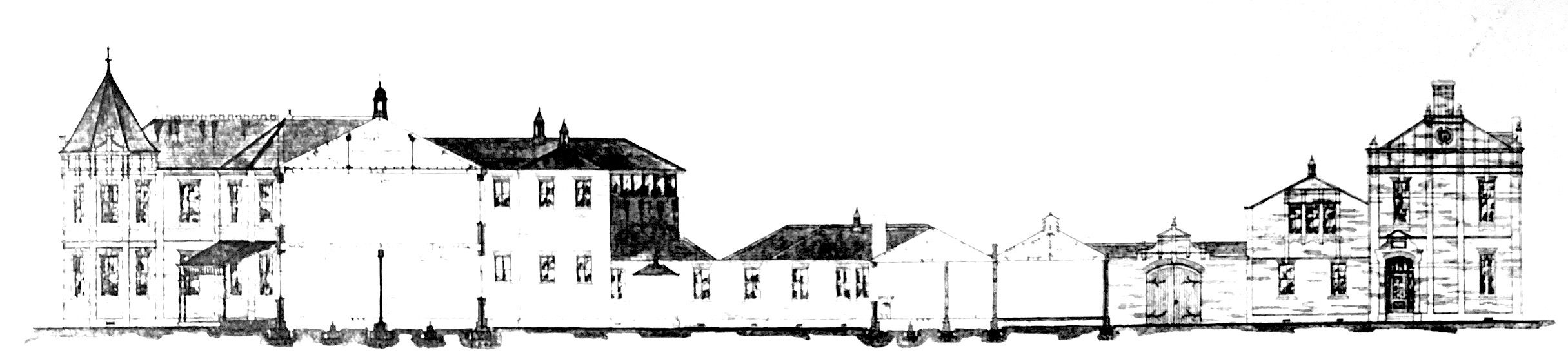

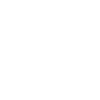

Porirua psychiatric hospital, ca 1910. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library

Porirua psychiatric hospital, ca 1910. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library

In the public imagination, the word “lunatic asylum” brings images of rattling chains, screaming patients, and sinister doctors.

There’s truth in that stereotype. Martin Sullivan and Hilary Stace put it like this in their Brief History of Disability in Aotearoa New Zealand:

“Mental illness was generally feared and misunderstood … The Porirua asylum mixed several categories of ‘undesirables’: those with mental health issues, intellectual impairment, disabled children, alcoholics, as well as elderly and homeless people. … For decades, all these ‘inmates’ also provided large captive communities for doctors and specialists to practise theories and treatments.”

But these brutal conditions were, in some ways, enabled by progressive ideas. Historian Warwick Brunton wrote that throughout the 1850s and 60s politicians and doctors pushed for “moral treatment” of lunacy. They argued physical restraints should be avoided in favour of “distraction” and “entertainment”.

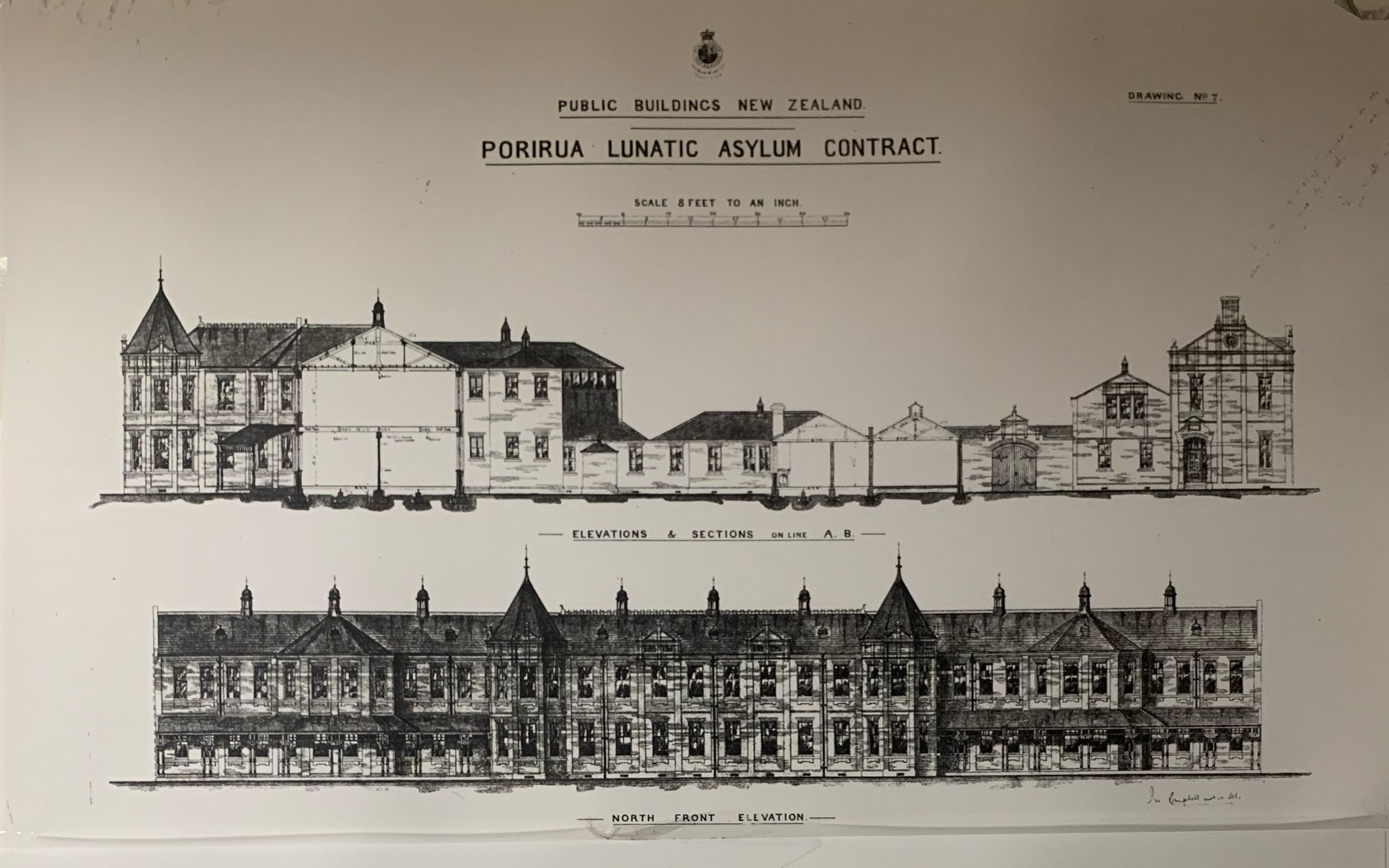

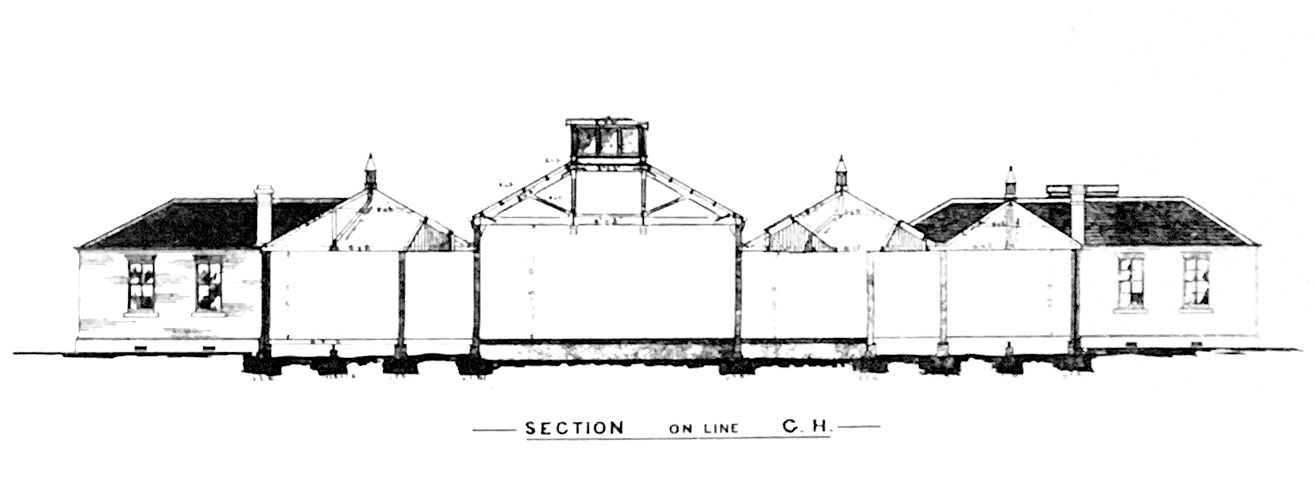

In the 19th century, asylums were seen as beneficial to the mentally unwell or disabled. The imposing architecture of places like Porirua Lunatic Asylum was actually intended to maximise the sunlight and fresh air available to patients.

Photo: Taranaki Daily News, 1900.

Photo: Taranaki Daily News, 1900.

In the days before modern psychiatric medicines a peaceful, secure location was seen as the best treatment for “lunacy”.

Brunton quotes the lay superintendent of the Dunedin asylum who wrote in 1864 that: “Patience, gentle treatment, nourishing diet, Cleanliness with light employment or Exercise goes far to recover the Lunatic and in Chronic Cases serves to make them Comfortable or even happy. Amusements for the insane are indispensable …and where space can be found in an asylum, a weekly concert with dance.”

That same year a select committee of the Otago Provincial Council argued “lunatics should be regarded by the state as objects of tender solicitude.”

“No pains or expense should be spared in ameliorating their condition. [The commission] wholly condemn their being treated as paupers or prisoners.”

However, there were still plenty of problems in 19th century asylums from a modern perspective.

One of the members of that 1864 select committee, Edward William Alexander, argued rich and poor patients should be segregated. He claimed “to mix indeterminately, men or women holding good positions, with the insane poor, would be revolting to the feelings of friends, and detrimental to the recovery of the former class.”

The dark shadow of eugenics

Disability historian and advocate Hilary Stace believes things took a more sinister turn in the second half of the century, in part because of a new focus on education.

The 1877 Education Act mandated free, compulsory education for Pākehā children (education was also free for Māori children, but not compulsory until 1894). However, Stace points out this created more anxiety about intellectual disability.

“The more we had testing, the more we had those sort of ways to judge people and their abilities, the more there was found that there were people who weren't meeting some ideal standards of what should be expected from people,” she says.

Dr Hilary Stace at the Royal Commission into abuse in care hearings, 2022. Photo: RNZ / Katie Scotcher

Dr Hilary Stace at the Royal Commission into abuse in care hearings, 2022. Photo: RNZ / Katie Scotcher

These anxieties intersected with the global rise of social darwinism and eugenics as powerful intellectual movements. It was increasingly believed things like mental illness, disability, criminality and poverty had genetic causes - and that it was possible to breed these things out of society.

New Zealand played its part in this international intellectual movement. In 1903, the Wellington politician and doctor William Allan Chapple published an influential pamphlet, The Fertility of the Unfit, outlining his solution to the ‘problem’ of ‘defective’ individuals.

“The State can arrest the gradual degradation of its people, by sterilizing all defective women and the wives of defective men falling into the hands of the law … No woman in the child-bearing period of life should be released from an Asylum, until this operation has been performed. If a man is committed, his wife should have the option of divorce or be sterilized before his release.”

Chapple’s arguments were popular among the ruling classes, Stace says.

“We have a group of very privileged white people deciding what groups should and shouldn't be allowed to actually breed.”

But New Zealand’s eugenicists faced stiff resistance to their idea of a compulsory, state-run sterilisation programme, especially from some religious organisations. Ultimately, their suggestions were rejected.

However, Stace says they won a different victory with the passage of the 1928 Mental Defectives Amendment Act. This act was championed in part by Dr Theodore Gray - a former chair of the short-lived New Zealand Eugenics Board.

“Theodore Gray, was a very influential head of the mental hospitals department at that time and [he] wanted sterilisation,” Stace says.

“He didn't get his way with sterilisation, but he got to set up the first sort of farm colony, which was Templeton.”

Templeton was New Zealand’s first “psychopaedic institution” - focused on the long term care and confinement of ‘feebleminded’ children. This category generally included kids with intellectual disabilities, neurodiversity, and conditions like epilepsy. It also often included children who were simply from poor families and were having trouble at school.

Over time, authorities disproportionately targeted Māori and Pasifika children for institutionalisation. The Royal Commission's interim report estimates that by the late 1970s, about one in every 14 Māori boys and one in every 50 Māori girls was living in state institutions.

In his testimony to the commission the late Māori lawyer and academic Dr Moana Jackson said: “In my considered view [the reasons for the disproportionality] are unavoidably linked to the history of colonisation and the failure of successive governments to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi.”

Stace says parents, Māori and non-Māori, were often told their “feebleminded” children would be “happier among their own kind”. However, she argues these institutions were motivated more by eugenic ideals than the happiness of kids.

“The idea of institutions was firstly, you got them out of society. So they stopped being a risk, particularly for reproduction, and these ‘bad’ genes taking over the ‘good’ white population. They would be totally contained for their whole lives.”

Children were committed to institutions as toddlers or even infants, and the number of patients increased rapidly. Stace estimates that by the 1970s, two percent of New Zealand’s population was institutionalised.

“Templeton at its height had hundreds of young people, and then of course they never left,” she says. “That pattern was repeated around the country. There were little units and there were the big institutions like Lake Alice, which was founded in 1950, but has a terrible, terrible history.”

This “terrible history” at Lake Alice and other institutions has been documented in recent years thanks in part to the testimony of former staff and patients at the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in State Care.

In her testimony, former Porirua Hospital patient Beverly Wardle-Jackson said: “Every day, violent incidents would occur somewhere, usually ending with the nurses assaulting patients and dragging them off to the rooms, kicking them and punching them along the way. It was all wrong, so wrong, but there was no one to tell, no one to complain to.”

Even seemingly innocuous activities like bathing and toileting patients could be abusive experiences, Stace says.

“Quite often you hear stories from nurses that to wash them all, they had group washing.

“You just put the firehose on them, all of the whole room full of people. And even though the nurses, some nurses didn't like doing that and they thought it was wrong they did it - because they were told to do it. But also because they're [patients] not like us. They're different. They're lesser humans.”

The ‘safety’ argument

Some former nurses had complex feelings looking back at the ways patients were treated.

In 2003, two former nurses at Porirua Hospital, Rita and Ngaere, reflected on the conditions in a Radio New Zealand documentary.

They discussed how patients in the 1930s and 40s were locked in rooms where they slept under piles of straw.

“It looks terrible,” Ngaere admitted. “But what would you have done under the same circumstances? The patient had to be safe, had to be secure, had to be warm – wouldn’t keep clothes on. There was nothing else really that you could do. At least they were safe, and so was everybody else. And that’s what a lot of people seem to forget that everybody else was safe as well as the patient.”

The challenge of managing patients with severe mental health problems in an era before modern psychiatric medicines shouldn’t be underestimated.

At the time Rita and Ngaere worked at Porirua Hospital the only drug available was a sedative called Paraldehyde. “The whole place stunk of it” Rita remembered, “ghastly”.

But even after the 1970s, when effective medicines and management methods became increasingly available, concern over safety was a major obstacle to the disability rights movement, Stace says.

“The idea about safety is always used to justify, some extreme restraint or seclusion,” she says.

“Actually it's not a long term solution. It only causes more trauma, whereas there are other ways. It's complicated, but it can be done. And there are dozens of New Zealand young people and adults with high needs living in the community with well-trained carers.”

The hard end

It took a three-decade battle to bring institutionalisation to an end.

“The last institution to close was Kimberley,” Stace says. “It didn't close till 2006 and there was huge opposition from the parents and family members group because again, they thought they were safe there.”

Fears about deinstitutionalisation were sometimes justified.

“There were some not very good stories of the deinstitutionalisation process,” Stace says.

“From getting good new accommodation … proper care and support and acceptance from their new communities. All those things were slow and quite tricky to do.”

Among those who took part in the struggle to reintegrate institutionalised patients was retired GP Dr Richard Medlicott. He treated many former patients after they left the institutions in the 1990s.

“One of these guys had just been a bit slow when he was eight and ended up at Cherry Farm [psychopaedic institution],” Medlicott recalls. “[He] came out when he was 65.

“How do you take those people and reintroduce them into society? Going to the shops. What we think of as normal life. It happened, and thank goodness that happened. But it was a challenge.

“Hopefully, we won't have to do it again. Because we won't have people living this way.”

Feature stories from Nellie's Baby

-

In search of a missing sister

-

Where ‘those sorts of people’ were sent

-

The law that banned sex for the “mentally defective

-

‘Someone must know something’: One woman’s story of an adoption, an asylum and a search for the truth

-

‘It was an evil, evil place’: How a refuge for the mentally ill became a nightmare

-

Nellie and me: Unravelling the story of a life inside an asylum

Listen to the Nellie’s Baby

podcast now on

Apple

Spotify

iHeartRadio

or wherever you find podcasts

Writer / Presenter:

Kirsty Johnston

Executive Producer:

Tim Watkin

John Hartevelt

Producers:

William Ray

Justin Gregory

Sound Engineers:

Phil Benge

William Saunders

Justin Gregory

Marc Chesterman

Production Coordinator:

Briana Juretich

Visuals:

Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Angus Dreaver

Design:

RNZ